Food For Thought

It’s a windy September Saturday as Joe Ingrao ’16 strides across Lafayette’s Community Garden and Working Farm like a hippie drill sergeant. He doesn’t scream orders at the 20 students under his command so much as convince them what he’s telling them is a pretty good idea.

They look up from the greens, peas, pumpkins, and yellow squash they are picking to better hear him. “Harvest the kale in bunches of eight to 10 leaves,” says Ingrao, his dark curly hair tightly bunched in a ponytail beneath a tan Army cap.

“Should we avoid the ones with holes in them?” asks Molly Leech ’17, an anthropology and sociology major, who grew up tending her family’s vegetable garden. The produce, destined for the kitchens of campus dining halls, has to be in good condition.

“You should avoid the ones that are completely chewed up,” he replies. “A few holes are OK.” This is, after all, an organic farm and it doesn’t use the pesticides that many other farms employ to keep their produce hole-free but residue-heavy.

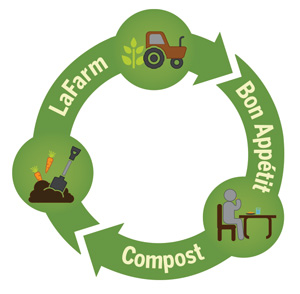

When Ingrao isn’t sporting a hydration backpack and riding herd over a bevy of veggies, he heads Lafayette Food and Farm Cooperative or LAFFCO, a student organization formed last spring to support LaFarm. This two-acre field is three miles north of campus and is the locus of the College’s sustainable food loop.

More than 2,000 pounds of produce were harvested there last year, but LaFarm is much more than a source of healthy food; it’s a living laboratory where students conduct research on ways organic growing practices enhance the soil, study pollinator species protection, and work on eco-friendly designs for a low-footprint greenhouse.

Feed The World, Buy Local

Joe Ingrao ’16 is researching greenhouses at college farms for a paper he’s co-writing with Prof. Benjamin R. Cohen.

The growing season is almost over, but interest in food—specifically locally sourced, sustainable food—at Lafayette and academic institutions nationwide is at an all-time high and a reflection of a growing national movement. It’s a story that’s gaining ground in campus kitchens where college and university food service providers are moving from plates of processed grub toward fresh, healthy meals. And those providers are buying local. Lafayette’s dining supplier, Bon Appétit, is a perfect example of the farm-to-school model. Each month, John Soder, the company’s executive chef at Lafayette, buys about $20,000 worth of produce from 14 area farms and suppliers. In Pennsylvania he gets potatoes from Twin Maple Farms in Bath; butternut squash and garlic from Scholl Orchards, in Bethlehem; and hard wheat flour for pizza dough from Castle Valley Mill in Doylestown.

“People are just becoming more concerned about where their food is coming from,” says Alexa Gatti ’16, president of Lafayette Environmental Awareness and Protection (LEAP). “It’s definitely an important issue for my generation.”

Welcome to the most current version of the environmental movement; a more engaged iteration of the one that began 40 years ago. A stereotypical view of that era has young idealists flocking to the countryside for a more simple existence away from the ills of mainstream society, says Benjamin R. Cohen, assistant professor of environmental studies and environmental science, author of Notes from the Ground and co-editor Technoscience and Environmental Justice.

Many of the environmental threats of that time—smog, toxic waste dumps like Love Canal, and rivers polluted by industrial runoff—have retreated in the public’s mind, only to be replaced by fears about food insecurity and climate change. Today’s food movement is less about distancing oneself from society and more about changing it by producing such things as juicy organically-grown heirloom tomatoes in one’s own backyard. It’s about looking hard at poverty and politics, policy and economics, big agriculture and fuel-intensive infrastructure. It’s also about improving access to affordable, healthy food, and growing communities where members support and nurture not only each other, but the planet.

“It’s about seeing food reform as a function of societal reform,” says Cohen, a founding member of the newly formed Lehigh Valley Food Policy Council (LVFPC) whose mission is to grow the local food environment of the Lehigh Valley. Some of Cohen’s students generate projects with the potential of being heard by LVFPC, like the one undertaken by Ingrao, who is coauthoring a paper with Cohen on the benefits of greenhouses at college farms. Two other students, Miranda Wilcha ’16, and Peter Todaro ’17, members of the College’s first Digital Humanities Internship program, created GardenofEaston.org, a web site that aggregates local farmers’ markets, community gardens, food assistance programs, and other food resources for Lehigh Valley residents.

Have Veggies, Will Travel

Peter Todaro ’17 and Miranda Wilcha ’16 at the Easton Farmers’ Market

“Miranda and I found clear evidence of residents struggling to consistently find fresh food in some areas of downtown Easton,” says Todaro, a government and law major. “You can see how many people shop for food at the Dollar Store downtown, which only sells canned and processed food. There’s nothing fresh.”

Providing nutritionally rich food to under-served residents in the city’s West Ward has been the focus of the College’s Technology Clinic, which has worked with the West Ward Neighborhood Partnership on several projects over the last decade. The West Ward is considered a food desert because it matches that term’s criteria; 20 percent of the neighborhood’s households don’t have a vehicle and the closest grocery store with fresh produce is at least two miles away.

Tech Clinic’s first project with WWNP was run in collaboration with Easton Area Community Center and Easton Middle School, and involved teaching people how to build “bucket gardens” in cheap, low-tech, high-yield containers, says Lawrence Malinconico, director of the Tech Clinic, a year-long course in which teams of six students from different majors work to solve real world problems.

“Students got involved nurturing these seedlings and then at the end of the school year, they got to take the plants home and have produce growing on their back porch,” Malinconico says. “We called them pizza buckets because they grew tomatoes and green peppers, which are great to put on pizzas.”

More recently, Sophia Feller, Urban Agricultural Coordinator of WWNP asked Tech Clinic students to consider why residents weren’t coming out to harvest produce at the Urban Farm in Southside Easton and other pocket gardens throughout the West Ward. “Tech Clinic was charged with the challenge of ‘if people aren’t coming to the vegetables, how can we get the vegetables to the people?’ ” says Malinconico, associate professor of geology and environmental geosciences.

Enter the Veggie Van, otherwise known as Malinconico’s white Toyota Tacoma truck. It was one of several vehicles used to transport vegetables grown at the Urban Farm, community gardens, and LaFarm to West Ward residents. This past summer, students changed the name of the project to Veggie Stand to better reflect the method of distribution at the 10th and Pine Streets site. Students manage all aspects of the 18-week summer program, including planting, weeding, watering, harvesting, packing, and delivering vegetables.

The project has been wildly successful with the community. “We distributed almost three tons of produce and served 80-plus people,” says Malinconico, noting that significantly more people benefit than those who directly receive the vegetables (for a suggested donation of $5). The Veggie Stand ensures that entire families get essential vegetable nutrition they can’t find in West Ward corner stores. Any excess produce is donated and delivered to Easton’s food banks.

Feed Your Head

Rachel Young ’18 hands out vegetables grown at LaFarm to residents of the West Ward.

The Veggie Stand and LaFarm may be small projects—but that’s exactly what makes them so locally effective, says Cohen. “Both efforts were designed in collaboration with the community, which researchers show is a key way to addressing food security projects.” What’s more, the ventures have inspired students in meaningful, lasting ways. A number of students who worked at LaFarm before graduating, now work on farms and in farmer-training programs of their own. Others work in graduate programs pursuing further training in food security issues and sustainability.

Caroline Cohen ’13, an engineering studies graduate and no relation to Professor Cohen, spent the past two years studying and living in eco-villages in Scotland and Massachusetts, and is now working toward a master’s in environmental leadership at Naropa University in Boulder, Colo. A climate science course taught by Kira Lawrence, associate professor of geology, and department head of environmental science and studies, inspired Cohen’s career path.

“It became so clear to me that there were so many things that can be done to make a change,” says Caroline Cohen, noting courses with Lawrence, Ben Cohen and Julia Nicodemus, assistant professor of engineering studies, prepared her well for the rigorous coursework of her master’s program. “It’s not a pipe dream to think that there are things we can do to alleviate climate change and environmental degradation, but it’s painted in the media as a hopeless cause.”

Part of the College’s growth in attention to the necessity for more sustainable living was the introduction of two new majors in 2012, the environmental studies and environmental science degrees. Along with a host of parallel initiatives—a new community garden and farm, full-time professional farmer Sarah Edmonds (above), new professors, new classes and new relationships with the community—the scholarly and academic anchors allow the College to attract more environmentally minded and sustainably focused students, says John Wilson, laboratory coordinator for geology and geosciences.

“We certainly had the same type of students who were interested in the environment, but we probably lost many of them to schools with true environmental degrees,” says Wilson, who also operates a small working farm with his wife in Mount Bethel, Pa. “Now that we have this degree, Lafayette is a strong choice for them.”

Interestingly enough, and as a sign of the prominence of food as an important focus of study, this fall for the first time the College offered five First-Year Seminars dealing with food: Bread, 10 Ways to Know Nature, Global Food, and two sections of Feed the World: The Grand Challenge of Global Hunger.

The courses filled up quickly and all have met or exceed the 15-seat capacity. “Our students are really interested in making a difference and they know from watching the news and observing the world around them that we have very big issues that we need to confront in the 21st century,” says Hannah Stewart-Gambino, professor of international affairs and government and law, who is co-teaching Feed the World with Jennifer Stroud Rossmann, associate professor of mechanical engineering. “Issues of hunger include more than just absolute food deprivation, such as famines. Students also are interested in who has access to fresh food, vegetables, fruit, protein, or other nutrients vital to health and well-being.”

Stewart-Gambino and Rossmann decided to work together so they could create an interdisciplinary and collaborative experience for students. They also tapped into Easton’s neighborhoods via Bonnie Winfield, director of the Center for Community Engagement. In October, students dined with members from the Easton Hunger Coalition then interviewed them about food challenges. Afterward, students compared notes in search of starting points for projects with the potential to make an impact.

Back in the fields, the light begins to wane by 6 p.m. and Ingrao calls it a day by thanking all the students for their “stoop-ifying” efforts. Around them lies the fruit—and vegetables—of their labor: crates laden with softball-sized green squash, fat radishes, and dirt-glazed potatoes. He doesn’t know it at the time, but the harvest will be one of the last this year as an impending cold snap will shorten the harvest season. It’s not lost on Ingrao that a greenhouse, the very subject of his research—crafting sustainable small-farm infrastructure—could have protected the crops and prolonged the season. He’s confident it will happen one day, especially with the groundswell of support among students for food justice and sustainability issues.

For now it’s enough to have planted the seeds.