Student Research in the Spotlight

4:10 Student Research Poster Session

No. 7 Modeling Cardiovascular Flows: Lumped Parameter Model of Aortic Pressure

The human body’s circulatory system contains tens of thousands of miles of veins, capillaries, and arteries; studying and predicting that kind of complex network has its challenges. Remziye Erdogan ’20 (mechanical engineering) spent the summer working on a way to simplify the network.

The human body’s circulatory system contains tens of thousands of miles of veins, capillaries, and arteries; studying and predicting that kind of complex network has its challenges. Remziye Erdogan ’20 (mechanical engineering) spent the summer working on a way to simplify the network.

“This summer I did lumped parameter modeling of aortic pressure, which is basically a way to simplify computational models of the cardiovascular system and make them easier to interpret,” says Erdogan, who is working with Jenn Stroud Rossmann, professor of mechanical engineering, on the research.

By way of analogy, “we can use the same mathematical model for an electric circuit for the cardiovascular system,” she says. “The same set of equations apply to the cardiovascular system as they do for an electric circuit.” A pressure difference pushes blood through an artery in a similar way to a voltage difference pushing electrical current.

The aorta was selected for the study because it’s directly connected to the heart by the aortic valve and is representative of how other major arteries react during rest and exercise.

Erdogan says this technique is useful because the cardiovascular system is vast and complex. “Modeling cardiovascular flow using the electrical circuit analogy makes all the math much simpler to work with,” she says. “I was looking at what happens to the cardiovascular system when the body is at rest compared to it being in an exercise state. There are a lot of changes in the fluid dynamics of your blood when you exercise. The flow rate changes, blood pressure increases, and the heart rate goes up.”

Erdogan is excited about the work because it can be applied to the cardiovascular system in its entirety and with more refinement, and can accurately model blood pressure not only in the aorta but in other major arteries in the human body.

“Knowing how the cardiovascular system responds when these changes are made has big implications,” she says. “With this technique, you can develop broad models and look at trends throughout the entire body.”

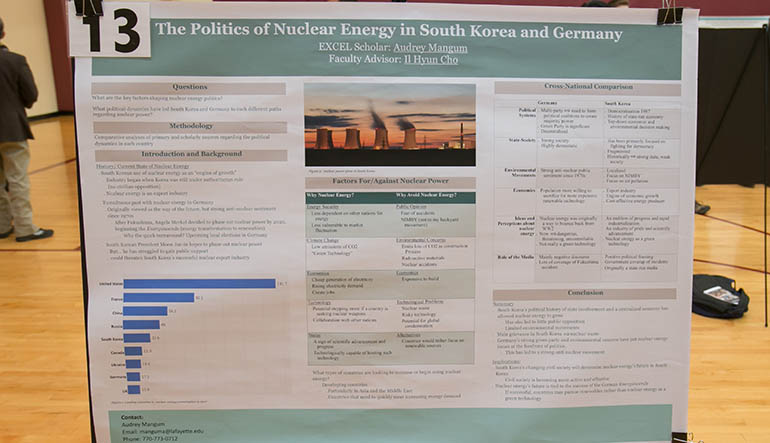

No. 13 The Politics of Nuclear Energy in South Korea and Germany

Two countries with strong economies and a history of using nuclear energy to power growth are pursuing different paths as political forces and public opinion shape perceptions of the nuclear industry.

Audrey Mangum ’21 (government and law, economics minor), assisted by her faculty mentor, Il Hyun Cho, associate professor of government & law and Asian studies, have been comparing nuclear energy policy in South Korea and Germany, both of which are being influenced by a variety of political, economic, and environmental factors.

“I specifically researched the key factors shaping nuclear energy politics and how the political dynamics of each country have led them to pursue vastly different paths regarding nuclear power, with Germany choosing to phase out nuclear power and South Korea’s continued use of nuclear power and success exporting nuclear reactors,” she says.

Germany’s historically strong environmental movement has placed nuclear power issues at the forefront of politics, leading to a strong anti-nuclear movement. Consequently, after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan, Germany decided to phase out nuclear power and begin its Energiewende (energy transformation to renewables).

“In contrast, South Korea began its nuclear industry while still under authoritarian rule; its history of top-down decision-making allowed for little public opposition and limited environmental movements until the 1990s,” Mangum says. “Civil society in Korea has been more focused on issues of democracy, rather than environmental concerns.”

Decisions made by both nations will ultimately have global implications, she notes.

“As South Korea’s civil society becomes more active and effective, it could alter its perception of nuclear power and, consequently, global perception of nuclear power,” Mangum says. “In Germany, the success of the Energiewende may very well determine nuclear energy’s future. If the transformation is successful, countries may begin pursuing renewables rather than nuclear energy as a green technology.”

No. 15 Punk, Poetry, and Peruvian Politics: Domingo de Ramos and Internal Armed Conflict

Punk is often used to invoke a music scene of spiked hair and mosh pits, but in Peru during the 1980s and ’90s it defined a social movement of artists, writers, and social dissidents, who, like the U.S. Beat authors of the 1960s, gave voice to the counterculture.

Research by Gabrielle Tropp ’20 focuses on Domingo de Ramos, a poet who was a member of Kloaka, the main group of writers who emerged from the Peruvian punk literary scene. “His poetry reflects the times and the conflict that was happening in that country, and its violence, but he also talks about the larger history of Peru,” says Tropp, who is working with Olga Rodriguez-Ulloa, assistant professor of foreign languages and literatures. “He was very much marginalized, basically the way all punks were at the time. But now he’s considered part of the literary canon of Peru.”

Topics he wrote about include the Shining Path rebel group’s strategic bombing of electricity towers, which brought blackouts to the city of Lima. Other poems talk about the imposed curfew, dealing with loss, and the apparent breakdown of society. “Because it was such a complex conflict, he wasn’t trying to cause change as much as express what it was like to be a young person living in a place torn apart by conflict for 20 years,” says Tropp, a Spanish and history double major.

Translating his poems can be difficult, Tropp says, because de Ramos has a penchant for making up words. That’s where Rodriguez-Ulloa comes in. She recently traveled to Peru to meet with de Ramos and is working with him on English translations of his poems.

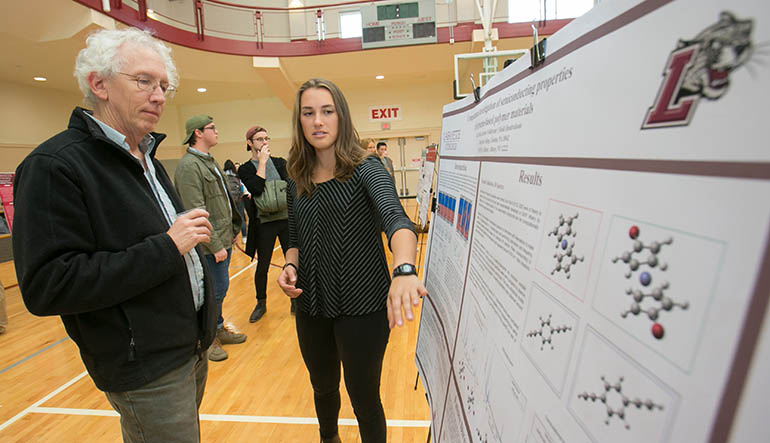

No. 16 Computational Investigation of Semiconducting Properties in Ferrocene-Based Polymer Materials

Solar power has incredible potential for the environment. And chemistry major Liza Welch ’19 wants to understand how the future of solar can be even brighter.

Welch spent the summer studying molecules that could improve the efficiency of solar energy production. At the heart of solar energy are photons, particles of light that excite electrons and set off a chain reaction that generates a flow of electricity. This process works smoothly when so-called “donor” and “acceptor” molecules that comprise the solar cell material interact with each other. But if they don’t physically mingle or mix, the process is hindered and less electricity is produced.

After learning two coding languages, Welch built computer models to make simulations that could then be tested and tinkered with in the lab. “If you can construct models that enable you to make representative predictions, then you can really fine-tune things,” she says. “You can simulate behavior, and you can do it in just a few hours. Gathering this kind of data from wet lab experiments would take much longer or may not even be possible, so computational work enables us to obtain molecular-level insight that can help shed light on complex processes.”

Welch plans to continue her research with adviser Heidi Hendrickson, assistant professor of chemistry, this spring. She’s excited about the possibilities for her own bright future. “Learning how to code this summer really opened up a lot of possibilities for me, I think,” she says. “It was quite challenging at first, but it actually made a lot of tasks easier now, and I can carry out calculations much faster than I could before. I’d really like to work for a startup that has a connection to tech and the environment. I think it would be really fulfilling to use my skills to make sustainable lifestyles and practices more accessible within local communities.”

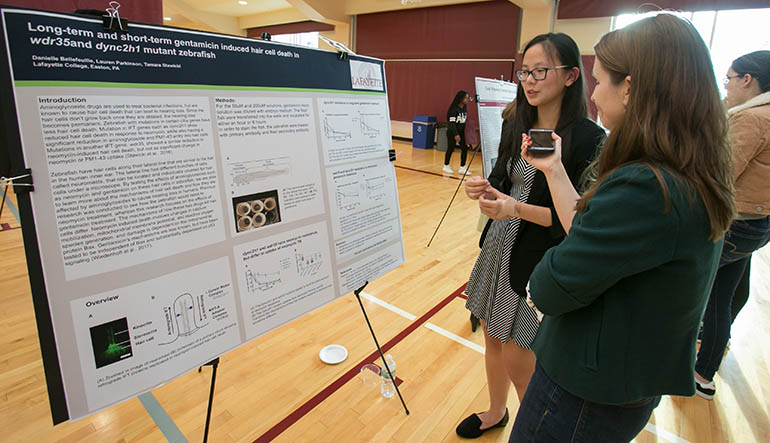

No. 21 Long-Term and Short-Term Gentamicin-Induced Hair Cell Death in wdr35 and dync2h1 Mutant Zebrafish

Gentamicin is a drug prescribed to fight bacterial infections. While it might be effective at killing staph and E coli, it can destroy sensory hair cells, the cells in our ears that detect sound.

To better understand the impact of this class of drugs and to see if hair loss can be avoided or reduced, psychology major Danielle Bellefeuille ’20 conducted research with Tamara Stawicki, assistant professor of neuroscience—and hundreds of zebrafish.

Zebrafish are a popular model for scientific study: They have been used to understand the biological processes and development of health afflictions, including muscular dystrophy and cancer. That’s partially because they grow at a very fast rate, developing from a fertilized egg to a swimming, sensing mini-fish within five days. They also are capable of producing hundreds of offspring in a short period of time, which gives researchers lots of subjects to study.

Bellefeuille’s role in the lab involved everything from feeding the fish, to checking the water temperature of tanks, to collecting fish eggs, to performing genetic testing. “The lab experience was really interesting,” she says. “Some of it was tough—we had to time things very precisely, and so I was setting timers and planning my day around which treatment needed to be given then. I learned a lot from the experience.”

The data collected showed that hair-cell loss is greater in a normal zebrafish than in mutant zebrafish, which is a significant finding. “While you can’t make a direct correlation between the fish and humans, zebrafish have a similar genetic structure to humans,” Bellefeuille says. “And so, we can learn a lot about the mechanisms of how cells uptake the drugs and better understand the process from a molecular level.”

No. 25 Fiction and Reality in Intelligence Agencies During the Cold War

How do you study the inner workings of the CIA if most of its documents are top secret? You read a spy novel.

That’s what Gwen Ellis ’20 and Joshua Sanborn, professor of history, are doing to trace how literary thrillers have shaped public perception of the agency during the Cold War as well as how the CIA has inserted its fictionalized self into operations. The pair also are looking at declassified documents for clues into the world of espionage.

“In these documents, normal spies are saying things like ‘that was really a James Bond operation,’ and ‘that went down just like it did in Casino Royale,’” says Ellis, a history and economics double major. “It’s a weird phenomenon.”

But that’s what the CIA does, right? It creates misinformation all the time, says Ellis, and because the agency is so compartmentalized, often times departments have no idea what colleagues across the hall are working on. “On one hand you have someone posting a fake thing about brainwashing and then another department picks it up and thinks it’s real,” says Ellis. “Then they start looking into brain- washing themselves when it all started as a fake report.”

And to keep track of its imagined persona, the CIA owns one of the most extensive collections of spy novels in the world. During the Cold War, the agency sponsored literary efforts and spent a considerable amount of money to do so.

Case in point that truth is often stranger than fiction.

5:10 p.m. Student Research Poster Session

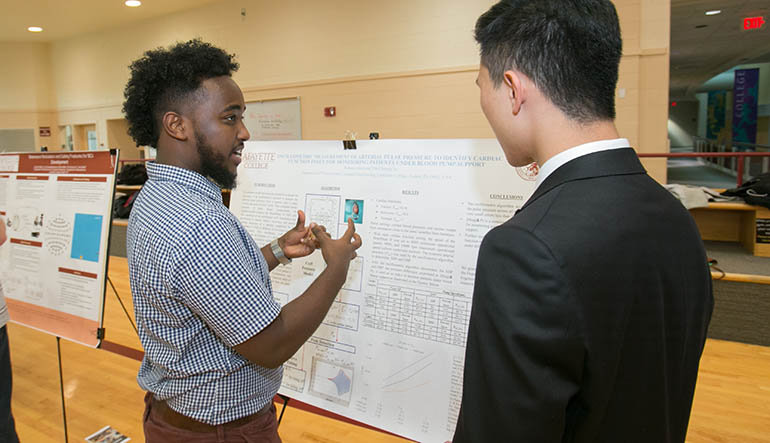

No. 5 Electrical Circuit Modeling and Simulation of the Cardiovascular System

Physicians who care for patients recovering from heart ailments traditionally rely on an echocardiogram to monitor cardiac function (or contractual state of the heart). But Robson Adem ’19 (electrical and computer engineering) and Yih-Choung Yu, associate professor and head of electrical and computer engineering, are researching a more cost-effective way to monitor blood pressure and measure the strength of the heart.

Their research uses an electrical circuit model to simulate the cardiovascular system, including electrical diodes as heart valves, electrical resistors as fluid resistance in blood vessels, electrical inductors representing fluid inertia, and electrical capacitors representing elasticity of blood vessels and heart chambers.

Solutions from mathematical equations represent blood pressures and flow rate of the cardiovascular system. One particular area of interest in this project is to simulate a diseased cardiovascular system supported by a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), which is implanted in a patient’s chest to help a diseased heart pump blood.

“Our goal is to use this model to formulate indices representing the healthy status of the cardiovascular system that can be detected without invasive sensors or costly procedures,” Yu says.

“By monitoring those index numbers, a physician can determine if a patient’s heart is recovering,” Adem adds. “If a patient’s heart is continuously getting better over time, physicians can then further assess his or her cardiac function through a cardiac imaging procedure, such as an echocardiogram. Less frequent use of cardiac imaging procedures to monitor a patient’s cardiac functions would save cost in the health care industry.”

Successful development of the research would allow clinicians to monitor cardiac functions of those patients supported by a LVAD with fewer cardiac-imaging procedures, which provides the advantages of less risk from LVAD support intervention, better freedom of movement, and lower cost of care.

No. 12 The Relationship Between Concentration of Immune Challenge in House Sparrow Nestlings and Parental Feeding Behavior

Emma Stierhoff ’20 never really considered herself a bird person, until last summer. From May through July, the biology major logged hundreds of research hours studying house sparrow nestlings at the Metzger Fields nesting boxes. “I was indifferent toward them before, but now I’m really fascinated by them,” she says.

Stierhoff, Julianna Carpenetti ’21, and adviser Mike Butler, associate professor of biology, are working to better understand how birds cope with immune challenges, such as parasites or bacteria, in the wild. To do that, they injected sparrows with various concentrations of dead bacteria that would trigger an immune response without harming the birds.

Stierhoff and Carpenetti monitored the nest boxes and recorded how often the nestlings were getting fed by their parents—the day before the injection, day of the injection, and day after. “We learned that the concentration of immune challenge impacts parental feeding rate,” Stierhoff says. “We hypothesized that the birds who had the highest immune challenge would be fed less; however, our data contradicted this. It was the birds who had a lower level of immune challenge that were fed less. We suspect that this might be because at the highest injection, the birds tolerate the bacteria instead of mounting an immune response. But with the lower injection, they did mount an immune response, which likely led to decreased begging and lower parental feeding.”

Their research is ongoing; Stierhoff and Butler want to continue collecting data to better understand if parental fitness and temperature also impact feeding rate.

“This was such a great opportunity for me,” Stierhoff says. “I got to design the experiment and carry out all the trials from start to finish. It was my first time doing that. It was such a valuable learning experience.”

No. 14 The Effect of Information on Public Support for Equitable School Funding

Would you support paying higher taxes if it meant more equitable funding for public schools? That was the question Jane Kirby ’19, Tali Dressler ’19, and Emma Novick ’19 posed to three groups of survey recipients.

“We looked at if more information would change their opinion on funding schools,” Dressler says.

The first subset of respondents served as the students’ control group and only received a statement explaining that the majority of funding for public schools comes from property taxes. The second group was provided an example of the funding gap. In Connecticut, Greenwich and Bridgeport school districts are located no more than 20 miles from each other, but Greenwich spends $6,000 more per student than Bridgeport.

The third group received a color-coded map of what school districts across the country spend per student.

“We found that treatment groups who received information about the inequality were more likely to support policies that leveled the playing field for all students by distributing revenue more fairly,” says Novick.

The majority of respondents in groups 2 and 3 also supported paying more taxes to fund public education, says Kirby, a government & law and psychology double major.

The trio conducted this study for a class taught by Mallory SoRelle, assistant professor of government and law, titled Inequality and the American State. They believe if elected officials distribute information about inequities in per-student spending and propose policies that align with residents’ financial preferences, they’ll ultimately “gain popularity” for reducing academic inequality.

No. 19 Anti-Genderism in Postcommunist Regimes

There is no word for “gender” in Hungary because it’s viewed as a foreign concept. Theologians in Poland have condemned gender theory, and Russia prohibits the “promotion of homosexuality.”

Rise of anti-gender campaigns beginning in 2000 in Eastern Europe is the research focus of Nicole Harry ’19 and mentor Katalin Fabian, professor of government and law.

“By anti-gender, we’re focusing on anti-LGBT rights and anything more or less going against the nuclear family ideal,” says Harry, who is double majoring in history and Russian and East European studies. “We’re noticing a correlation between anti-gender movements and right-wing authoritarian political movements in addition to a rise in religious movements.”

Hungary recently closed a liberal arts university that had a gender studies program and has instituted, along with Russia, academic censorship. Russia also restricts funding to NGOs devoted to LGBT issues, and in Poland, access to birth control and abortions has become increasingly difficult.

“These states are defined through ethnic boundaries so there’s a lot of nationalist sentiments in them,” says Harry. “Ideas of gender and different variations of it are also perceived as a liberal or western idea.”

No. 28 Perceptions, Prejudices, and Performances of Wokeness and Allyship

Are you woke? Are you an ally? Psychology and anthropology & sociology double major Bec Stargel ’20 worked with adviser Angela Bell, assistant professor of psychology, to uncover how these terms are interpreted among students on campus.

The concept of “wokeness” originated within the black community as a way to communicate being aware of social inequalities. An “ally” is someone who has societal privileges but wants to be a respectful partner and support those who are underrepresented.

Stargel’s survey of 143 students revealed that participants have a better understanding and awareness of wokeness than they do of allyship. Respondents also revealed they had more negative associations with wokeness versus allyship—with one interesting exception.

“People used words like ‘loud’ and ‘annoying’ to categorize woke people, but they said allies were ‘friendly’ and ‘will stand up for you,’” Stargel says. “However, people reported that they thought woke people were more intelligent and educated than allies. I found that really interesting.”

Another aspect of the survey focused on “performative non-prejudices”—people who pretend not to have racist attitudes because they want to be on the right side of a social issue. Stargel’s data shows that 20 percent of respondents said that they wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between someone who was pretending to not have prejudices and someone who was authentically not prejudiced. Stargel found this finding particularly fascinating. It’s an area of the research she plans to explore further as she continues to work with Bell in 2019.

No. 30 The Impact of Bushkill Creek Water Quality Change on Housing Price

During the heyday of the Industrial Revolution, Bushkill Creek, which meanders along Karl Stirner Arts Trail at the base of College Hill, was dammed at several points to provide hydroelectric energy to power mills.

Now obsolete along with the industries they once supported, the dams provide no economic or ecological benefits. In fact, they hinder water quality and habitat. A study showed that their removal would lead to numerous benefits to the creek, even beyond its banks.

Lauren Mathisen ’19 (economics and environmental studies), in research with Hongxing Liu, assistant professor of economics, looked at how removal of the dams and the expected improvement in water quality will be capitalized in the local housing market.

“Research found that dam removal will increase water quality and biological quality,” Mathisen says. “With all these positives and ecological benefits, there may also be financial benefits to the housing market in Northampton County.”

The research links housing transactions with water quality at the time to see the impact of water-quality change on housing price. Data shows that, on average, properties in Northampton County value more when water quality is better.

“With improved water quality, properties will be more desirable, and home buyers will be willing to pay more for them,” she says.

No. 35 Leafiness of Trees

If you don’t have a mathematics background, the title of this poster might give you an initial impression that Keith Vreeland ’20 is a biology major interested in botany. Those familiar with graph theory, however, would be quick to correct that notion, understanding the significance of a mathematical tree.

A tree is a graph or network in which there is exactly one path connecting two nodes. A leaf is a node that is connected to only one other node. With his adviser, Gary Gordon, professor of mathematics, Vreeland studied trees to determine the number of subtrees and number of leaves of those subtrees. With those computations, Vreeland could then define the overall “leafiness” of a tree. This enables them to calculate which trees are the leafiest and least leafy.

These findings can apply to many different fields—anything that relies on networks, including computer science, physics, chemistry, and linguistics. “I found this project so interesting because it applies to many things,” Vreeland says. “If you want everything connected to every other thing. Leaves are important because they are the least connected. So if you want to find the probability of just picking a leaf that’s only connected once, it can lead to some interesting results.”

Vreeland will present his research at the Joint Mathematics Meeting in Baltimore this month.